We need to talk about why EDI sent us in circles

by Ally Georgieva, Member of Diversity in Pensions and Head of Insights at mallowstreet

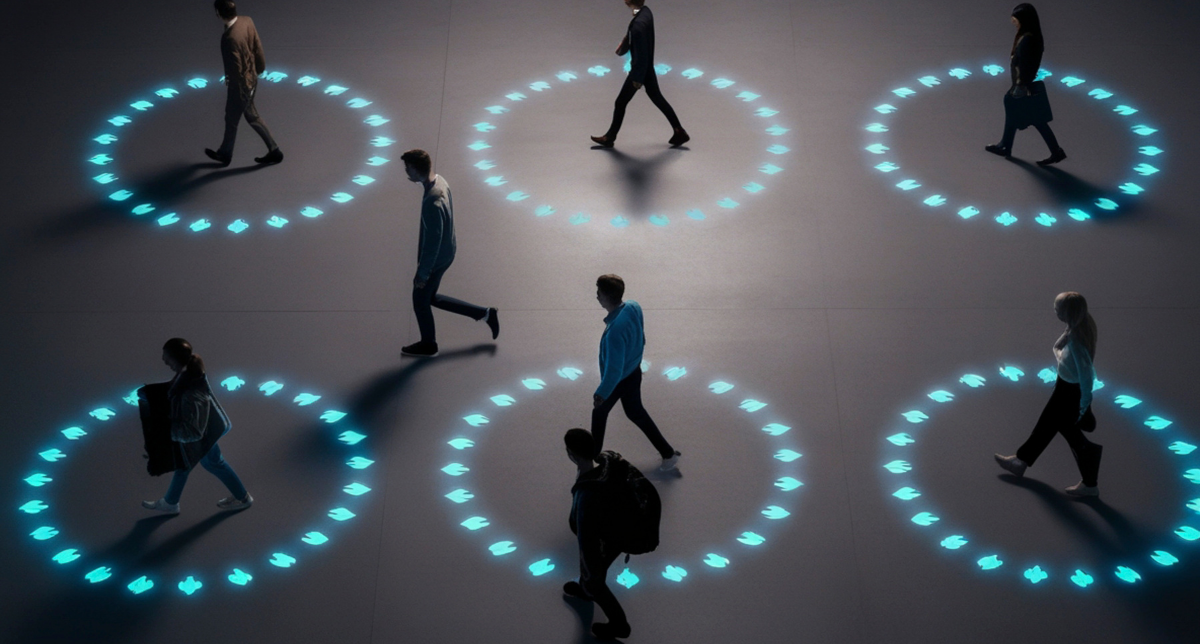

Cognitive diversity has become the go-to proxy for EDI — especially in investment and corporate settings where it feels more comfortable than talking about gender, race or background. But new research suggests this shift may have diluted what EDI was always meant to be: a framework for better access, stronger teams, and sound management. It isn’t dead, just mismanaged. This article explores the latest evidence — and why it’s time to rethink EDI as good management, not moral messaging.

Why meritocracy still needs management

A common argument is that diversity will emerge naturally in a meritocracy: hire “the best person for the job” and the rest takes care of itself. In practice, merit is about forward‑looking potential and contribution to a team, not just past achievement that is already on someone’s CV. It also assumes everyone has had equal access to opportunities to develop that potential — which is rarely the case.

Even when organisations genuinely hire the best, they still end up with differences in communication styles, personalities, values and working norms. Those differences need managing. Talent development, inclusion and psychological safety remain essential, because a meritocratic intake does not remove the need to help people contribute, challenge and thrive once they are inside the organisation.

The Alex Edmans paper on Cognitive Diversity in Asset Management does a fab job of systematising and naming elusive concepts that some of us understand only with our guts. It provides a framework of how to think through EDI in a completely different way that, ultimately, is just good management practice. And it starts with a simple idea: while we all expect others to think or be like us, we should start with the expectation of the opposite and work from there.

Cognitive diversity both improves and worsens outcomes

At its core, cognitive diversity refers to the range of perspectives, thinking styles, experiences and knowledge types within a team. It’s not a standalone concept, but one shaped by multiple factors — including, but not limited to, education, profession, personality, values, and life experience. That makes it broad and useful. But it also means the boundaries between cognitive, demographic and skill-based diversity are more blurred than most people acknowledge.

Cognitive diversity improves outcomes by broadening the range of ideas and interpretations on offer. It supports idea generation by adding more data points, more challenge, and more debate. It also aids idea sharing by reducing the pressure to conform and making groupthink less likely — especially where there is a strong culture of psychological safety.

But it can also slow things down. Diverse teams often find it harder to align — whether due to clashing communication styles, differences in how decisions are made, or a lack of shared language. These are not trivial issues. When not managed well, they can reduce trust, fragment decision-making, or discourage people from contributing at all.

Visible differences help people expect divergent and diverse opinions

Cognitive diversity isn’t something you can easily detect at interview stage. Skills diversity is — and it also has a bigger and stronger positive effect on performance. But not being skilled is equally valuable, as it gives team members a license to ask obvious questions and poke holes into the in-group’s consensus. This too is ultimately about complementary skill sets, and trustee boards comprised of professional and member-nominated trustees can best attest to this.

The other visible starting point is demographic diversity. Visible difference can help surface challenge — people expect disagreement and prepare accordingly. The idea that demographic traits (such as gender, ethnicity or age) are irrelevant to cognition is attractive to some, but rarely holds up in practice. People who claim to “not see difference” still find themselves baffled by generational shifts, or assume colleagues from other backgrounds have had it easier or harder than they did. That’s already an implicit admission that identity influences perspective.

Demographic diversity doesn’t guarantee cognitive diversity — it’s a weak proxy — but it can still encourage richer debate. Visibility matters. People are more likely to voice dissent when they see visual diversity in their group. This prompts them to expect disagreement and makes them more likely to dissent from the majority. Even when their input doesn’t win the day, minority or ‘out-group’ voices play a crucial role in surfacing risks and challenging consensus.

Creating the conditions for diversity to work

The research is clear: diverse teams perform best when innovation is the goal and psychological safety is strong. They benefit from the clash of ideas, from surfacing different interpretations and challenging groupthink. But they also need clarity — on expectations, roles, and decision-making. Not every meeting needs to be a strategy session. People need to know when to challenge, and when to align.

This is where affinity comes in — the natural understanding of and liking for those similar to us. People need to feel like they belong before they’re willing to offer dissent, and being part of a group helps, making retention, team cohesion and psychological safety as important as diversity itself.

Psychological safety doesn’t mean being soft. It’s not about avoiding conflict or pretending all ideas are equal. It means people feel safe to take interpersonal risks: raising a concern, admitting a mistake, questioning an assumption. Bad ideas are still challenged — but without fear of being undermined or excluded. And good dissent is actively welcomed, even if not always acted on. Teams that perform well typically know how to move between open-ended debate and focused coordination — generating ideas when needed, then shifting gears to agree next steps and execute.

There are practical ways to support this. For example:

- State clearly how much dissent is expected and when decisions will be made – so people don’t assume every challenge must be accepted.

- Use one-on-one conversations to surface quieter or dissenting voices, especially when group dynamics suppress honest feedback.

- Experiment with formats like silent-start meetings, anonymous voting, or post-meeting follow-ups to avoid premature consensus.

- Model the behaviour from the top – senior leaders can share their blind spots, ask “What am I missing?”, or invite feedback on past mistakes.

- Balance communication styles rather than forcing convergence. One person’s bluntness can coexist with another’s politeness – the goal is clarity, not conformity.

- Focus on substance over airtime – include subject matter experts when relevant, and design meetings for impact, not consensus theatre.

Time to move past the labels and do the work instead

Diversity without inclusion leads to turnover. Inclusion without challenge leads to groupthink. And equality without access to contribution leaves talent on the sidelines. The goal shouldn’t be to prove whether there is value in EDI. The real goal is to make all three work together — not in name only, but through deliberate effort and good management.

Yet in many organisations, the balance has tipped too far towards inclusion alone. Meanwhile, diversity gets watered down to “cognitive diversity,” and equality is avoided for fear of tokenism or misinterpreted as forced fairness. But the problem may not be with the principles — it’s with the language. Stripped of their labels, these ideas are just sound business sense.

| Traditional Term | Reframed Concept | What It Really Means | Why It Matters |

| Diversity | Broader ideas and perspectives | A mix of experiences, skills, thinking styles and backgrounds that shape how people see and solve problems | Improves idea generation, reduces blind spots, supports innovation — but only if managed well |

| Equality | Access to contribute | Ensuring everyone has a fair chance to participate, speak up, and develop — not just be “in the room” | Prevents talent from being overlooked; addresses structural gaps in opportunity and progression |

| Inclusion | Psychological safety | Creating an environment where people feel safe to share views and challenge ideas even if their idea doesn’t “win” | Enables dissent, encourages debate, builds trust — and is essential for cognitive diversity to add value |

Moving past the jargon doesn’t mean lowering ambition. It means making these concepts more practical, less polarising, and easier to embed in everyday management.

Focus on good management

Given the trade-offs, it’s worth asking why we are so fixated on proving a net performance benefit from EDI. Asset managers aren’t expected to outperform all the time — their contribution is judged over time and against multiple metrics. Value for money is not measured just on returns but also a variety of qualitative factors. The same should apply to diverse teams. Not every team can prove its worth through performance gains, especially when the evidence is mixed and difficult to isolate.

So this isn’t about one-off metrics — it’s about belief in the value of different perspectives, and the commitment to create environments where that value can emerge. The research shows it isn’t simple, and that both cognitive diversity and alignment have value, depending on the context. That’s not a failure of EDI, just a reminder that it’s not magic.

And if you forget the jargon and labels for a second, all this is just good team management: setting norms, encouraging challenge, and making sure people know they belong. Some teams act on those beliefs, others don’t. Which one are you?